Time moves only when you move.

That’s the premise of SUPERHOT VR, a virtual reality (VR) game that inadvertently taught me an important lesson about accessibility in virtual learning spaces. While playing, I found myself completely disoriented, losing track of my physical surroundings as my proprioception, my body’s sense of position and movement, became increasingly disconnected from reality. Friends had to repeatedly redirect me to prevent collisions with furniture and walls. This experience sparked a crucial question: If a relatively simple VR game could so thoroughly disrupt my spatial awareness, how might these technologies impact learners with different sensory processing needs?

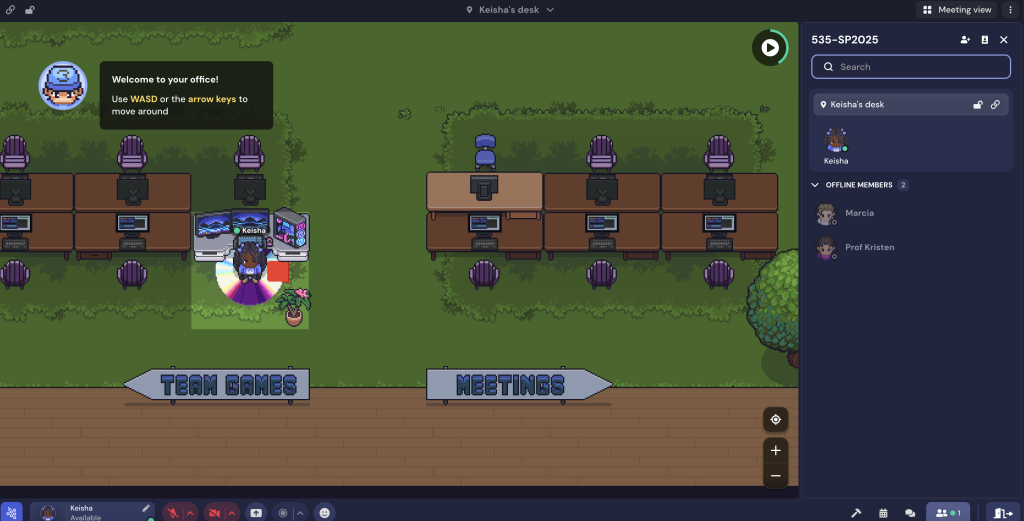

As educational institutions embrace virtual worlds, accessibility must be more than an afterthought. Studies show that nearly one-third of gamers in the UK and US identify as disabled, nearly twice the proportion of the general population. Yet, despite the growing presence of disabled users in digital spaces, many virtual environments remain inaccessible to this significant portion of our learning community. While platforms like Gather, FrameVR, and Meta’s Horizon Worlds promise immersive educational experiences, they often overlook fundamental accessibility considerations.

The Evolution of Virtual Learning Spaces

The landscape of virtual learning continues to evolve, with platforms like Minecraft demonstrating clear educational value, particularly in visualization-heavy subjects. However, many virtual environments remain in developmental phases, lacking sufficient features for effective, accessible learning that accommodates the full range of disabilities outlined in Yale University’s accessibility guidelines, from visual and auditory to cognitive and physical impairments.

Multisensory Design: Beyond the Screen

Lauren Race, Accessibility Designer at NYU’s Ability Project, emphasizes that “flat digital interfaces are never a complete replacement for touch, smell, or sound.” This insight highlights the need for multisensory design in virtual education. The most effective virtual environments engage learners through multiple channels simultaneously:

Visual + Tactile + Audio Integration

A virtual architecture lesson demonstrates this powerful combination: students explore 3D models with adjustable contrast settings while receiving haptic feedback that simulates different building materials. Spatial audio cues guide navigation, while text alternatives ensure information remains accessible to all participants. I’ve seen firsthand how these multisensory principles align with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in practice while developing accessible online nursing courses, where combining modern design standards with multiple modes of engagement significantly improved learning outcomes.

The stakes for getting this right are high. As Morgan Baker, Accessibility Lead at Electronic Arts notes, poorly designed interfaces can “make the product less enjoyable or force a player to completely stop… altogether.” This risk of exclusion makes thoughtful multisensory design not just beneficial, but essential.

Making Virtual Spaces Work for Everyone

Physical Access and Body Awareness

The physical demands of virtual reality create unique challenges. My experience with SUPERHOT VR highlighted how easily these environments can disrupt our physical orientation. Virtual learning spaces must support:

- Flexible input methods beyond standard VR controllers

- Options for seated or standing participation

- Customizable movement requirements

Managing Cognitive and Neurological Accessibility

The same immersive qualities that make virtual worlds engaging can overwhelm learners with attention deficit disorders, autism spectrum conditions, or other cognitive processing differences. Virtual spaces must adapt to various learning and processing styles, particularly for those who have difficulty processing sensory information like visual or auditory input (perceptual disabilities) or experience challenges with balance and spatial orientation that can lead to motion sickness (vestibular sensitivities).

Creating Cognitive Clarity

Virtual environments should offer customizable experiences that support different processing speeds and attention spans. Essential features include adjustable pacing for content delivery, clear navigation markers for those with memory impairments, and simplified interfaces for learners who struggle with complex visual information. The goal is to maintain engagement while preventing cognitive overload.

Visual and Auditory Access

Virtual environments must serve learners across the spectrum of visual and auditory abilities. For those with visual impairments, the environment should provide:

- High-contrast display options and adjustable text sizing

- Screen reader compatibility for blind learners

- Colorblind-friendly design schemes

- Alternative text descriptions for visual content

Supporting deaf and hard-of-hearing participants requires thoughtful audio alternatives. This means going beyond basic captioning to create a fully inclusive audio experience through:

- Real-time captioning with speaker identification

- Visual indicators for important audio cues

- Individual volume controls for different sound elements

- Clear visual feedback for interactive elements

Communication and Speech Support

Virtual learning environments must accommodate diverse communication styles and abilities. For learners with speech impairments or those who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices, text-based interaction might be preferred. Others with auditory processing disorders benefit from written instructions alongside verbal ones.

The key is providing multiple pathways for participation—whether through text, voice, or visual signals—while ensuring that no single communication method becomes a barrier to engagement. This flexibility creates a more inclusive environment where everyone can participate in ways that work best for them.

Designing for Success

The most effective virtual learning spaces maintain a careful balance between innovation and accessibility. Consider these key principles:

Foundation for Inclusive Design

- Start with accessibility in mind, not as an afterthought

- Regularly test with diverse user groups

- Maintain options for different technology comfort levels

Integration with existing assistive technologies remains crucial. Features that support accessibility enhance learning for everyone: clear navigation, multiple communication channels, and adjustable content delivery benefit all students in the virtual classroom.

Looking Forward

As we continue developing virtual learning environments, we must ask ourselves: How can we ensure that our pursuit of immersive education doesn’t create new barriers for learners? The answer lies in embracing multisensory design principles and maintaining constant dialogue with our diverse learning community.

Virtual worlds offer unprecedented opportunities for educational innovation, but their true potential can only be realized when they’re accessible to all learners. As Lauren Race reminds us, “Accessibility design is about options and meeting people where they are.” Let’s build virtual learning spaces that truly embody this principle.